A Hope For The Future

A light at the end of the tunnel: Is it possible to cure MS?

If you Google, “cure MS” the response remains consistent: “There is no cure for MS”, a consensus shared by the most prestigious research centers and patient associations. Even ChatGPT responds “there is currently no known cure for MS” (January 2025).

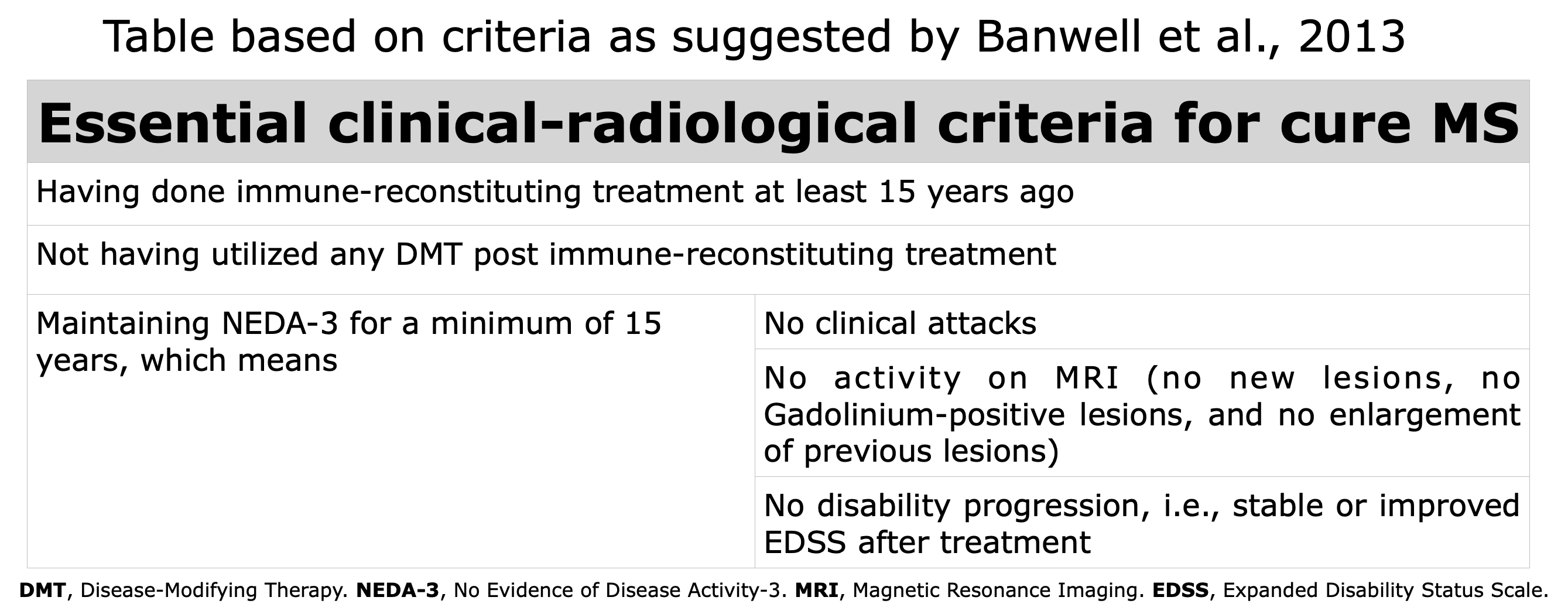

However, some patients, with a certified diagnosis of MS, experience a clinical condition that is very close to their MS having been “cured”. After undergoing transplant, an immune reconstitution therapy, they have been living for years, some for two decades now, in a clinical situation defined as NEDA3 (Havrdova et al., 2009). This means no clinical attacks, no new activity on MRI, no accumulation of disability, and, of course, without taking the usual MS DMTs. These patients who are treatment-free and NEDA3 for at least 15 years, can be defined as “cured” according to a working definition (Banwell et al., 2013).

AHSCT has the potential to eliminate the immunological mechanism causing lesions in the CNS and to renew the immune system, making it less aggressive towards the CNS.

We want to clarify that previous disability or deficits that have been present for a long time cannot be improved by AHSCT. For more information, please read “AHSCT as a cure” section.

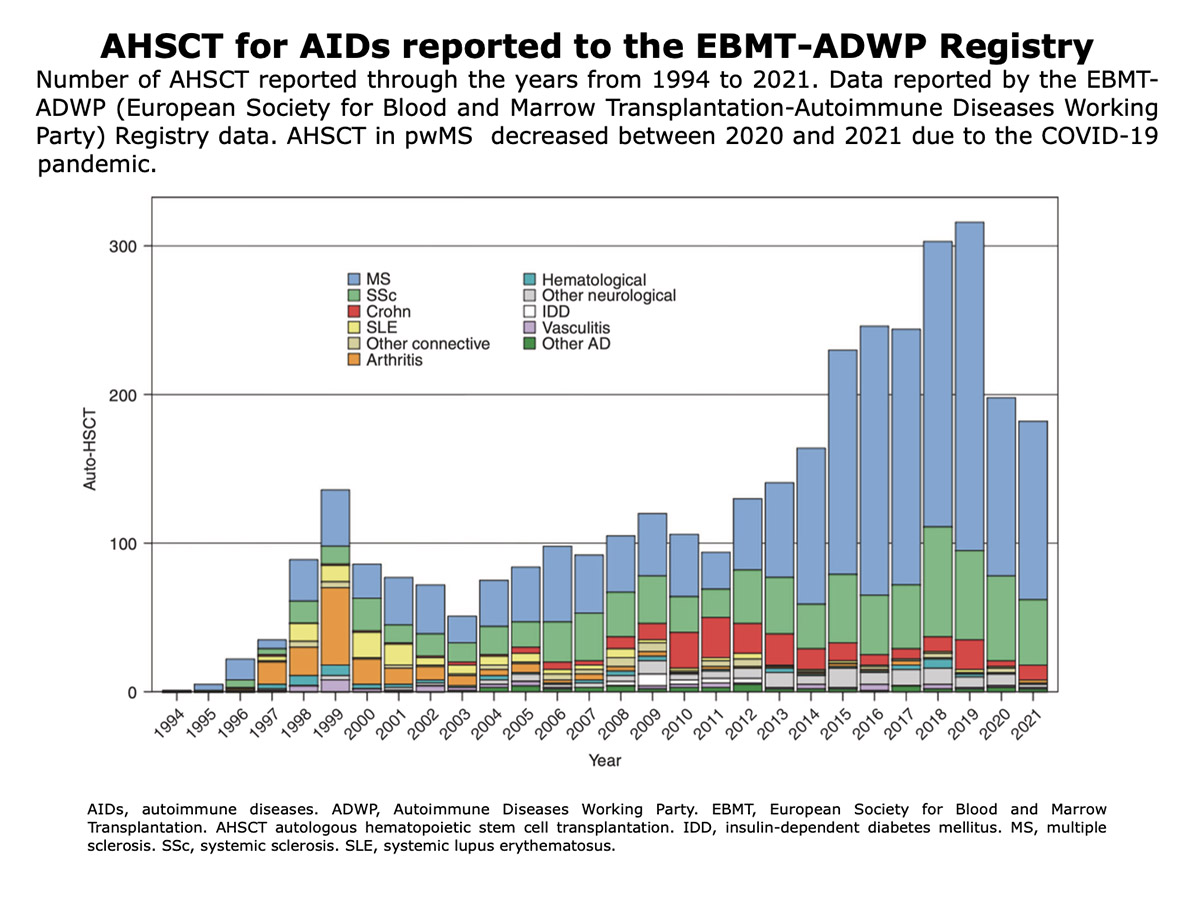

How many patients have undergone AHSCT worldwide?

We estimate that the number is over 4000; this figure was obtained by summing the cases reported in retrospective studies, meta-analyses, and systematic literature reviews. Bayas et al., 2023 | Zhang and Liu, 2020 | Patti et al., 2022 | Willison et al., 2022 | Nabizadeh et al., 2022.

Figure from Alexander et al. “Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and cellular therapies for autoimmune diseases: overview and future considerations from the ADWP of the EBMT“. Bone Marrow Transplantation (2022).

Why Cure?

Why the term “cure” is written in quotation marks on this website?

We use quotation marks with the term “Cure” or patients “cured”, to emphasize that it refers to a working definition that may prove wholly or partially incorrect in the future. Moreover, the quotation marks also serve as a signal of caution and realism, to avoid illusions and unrealistic hopes.

The road to curing MS is long, winding, challenging, and full of disappointments and risks, but it is navigable: we must make every effort and encourage research in that direction.

It should be emphasized that a person who is “cured” of MS still has the risk of their MS reappearing, just as being “cured” of cancer does not exclude the risk of cancer recurrence.

Word Cure Enters MS World

The purpose of this website is to promote therapeutic strategies that may lead to the “Cure of MS”, while maintaining a pragmatic and realistic standpoint.

In 2020, Lycke and Axelsson posed a pertinent question: “Can multiple sclerosis be cured?”. In response to this question, Giovannoni et al. stated that “with an answer to Lyke and Axelsson; yes we can cure MS but we have to define precisely what we mean and the caveats we need to discuss when we say to someone with MS that they are cured.” (Giovannoni et al., 2020).

One must exercise caution before discussing the “Cure” of MS”, and neurologists, correctly, have never used the word “Cure” in the daily management of patients. Recently, however, the term “Cure” has started to appear in scientific conferences. Some examples and a personal anecdote.

- In May 2023, the annual scientific conference of the Italian Multiple Sclerosis Association (AISM) was titled “Our pathway to cure”.

Annual Scientific Congress organized by Italian MS Society and Its Foundation, titled “Our Pathways to Cure” held in Rome 30 May-01 June 2023.

- The main scientific presentation at the global MS conference in Milan in October 2023, ECTRIMS 2023, delivered by Stephen Hauser (Robert A. Fishman Distinguished Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco UCSF), one of the most renowned global experts on MS, titled his presentation “MS: Pathway to a Cure”.

- The personal anecdote refers to the MS Conference held in Cuneo in February 2023, where I had the honor of giving a lecture titled “Slowing, freezing, curing Multiple Sclerosis”. It was the first time I used the word “Curing” in a presentation, and I recall the benevolent curiosity of some colleagues while reading the program.

“Everyday Miracles: Curing Multiple Sclerosis, Scleroderma, and Autoimmune Diseases by Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant” by Prof. R.K. Burt published in January 2023 by Forefront Books.

The possibility of “Curing MS” is also discussed in the book by Richard K. Burt, titled “Everyday Miracles: Curing Multiple Sclerosis, Scleroderma, and Autoimmune Diseases by Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant” published in January 2023 by Forefront Books. The author, a Fulbright Scholar, Professor at Medicine at Scripps Health Care, tenured retired Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, USA; is one of the foremost experts in the use of AHSCT in autoimmune diseases. In his book, Burt recounts how, over 35 years of work, he developed and refined the AHSCT procedure for autoimmune diseases, including MS, and shares the stories of some of his patients who have been living symptom-free for over 20 years after undergoing AHSCT.

Working Definition of Cure

If we assume that it is possible to cure MS, what clinical, radiological, and biological characteristics must a person with MS have to be defined as “cured”? And how long must they remain in such a condition? How should the therapy capable of curing MS act?

The first time, to my awareness, in which the prospect of curing MS was introduced in scientific literature dates back to 2013, in an editorial by Banwell, Giovannoni, Hawkes, and Lublin, the editors of the journal Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders (Banwell B. et al., 2013).

While discussing the likelihood that the drug Alemtuzumab, an immune-reconstitution therapy, could sustain a state of NEDA3 for numerous years, the four editors pondered the working definition of “Curing MS“. They concluded that maintaining the NEDA3 condition for 15 consecutive years after completing treatment would constitute an acceptable definition. Why 15 years? This is because, after 15 years of NEDA3, the probability of disability progression is notably low; indeed, the median time to the onset of Secondary Progressive MS is 10.4 years (Kremenchutzky et al., 2006).

Starting from the working definition elaborated by Banwell et al., in 2013, we can enumerate the characteristics that an individual must possess to be defined as “Cured”, emphasizing that there is always the possibility of the recurrence of MS, even in those who meet all the criteria, even after many years.

Table based on Banwell et al., 2013.

Like all working definitions, this one can be updated and modified as driven by ongoing studies and emerging insights. Consequently, additional criteria that may, with additional research, be incorporated into the Banwell criteria include the following:

- Rate of progression of brain atrophy comparable to healthy person (NEDA4)

- Biological markers: sNfL and/or GFAP within normal ranges (NEDA5)

- Immunological reactivity against the CNS as in healthy person

Other criteria under investigation:

- Reduction/disappearance of oligoclonal bands in cerebrospinal fluid

- Reduction/normalization of the cerebrospinal fluid K index

- Absence of SELs on MRI

- No appearance of new lesions with a paramagnetic ring on MRI

- Reduction/disappearance of the symptom “fatigue”

This working definition of “Curing MS” should be regarded for what it is, namely, a definition adopted temporarily to facilitate communication or understanding.

Working definition: the term “working” implies that this definition is practical and functional for the specific task at hand. It may not be the final or exhaustive definition, but it serves the purpose of enabling progress, discussions, and/or actions in a particular project or area of research (from ChatGPT, October 2024).

NEDA & Sustained Remission

In 2020 Giovannoni et al., raised an important question “Defining a cure in MS is difficult. How long should we wait 15 years, 20 years, 25 years or more before claiming a cure?”. Then “We have previously proposed defining an MS cure as NEDA, or no evident disease-activity, at 15 years as a starting point. We justified using the 15 years time points (Banwell et al., 2013) as it is a commonly accepted time-point for defining benign MS”.

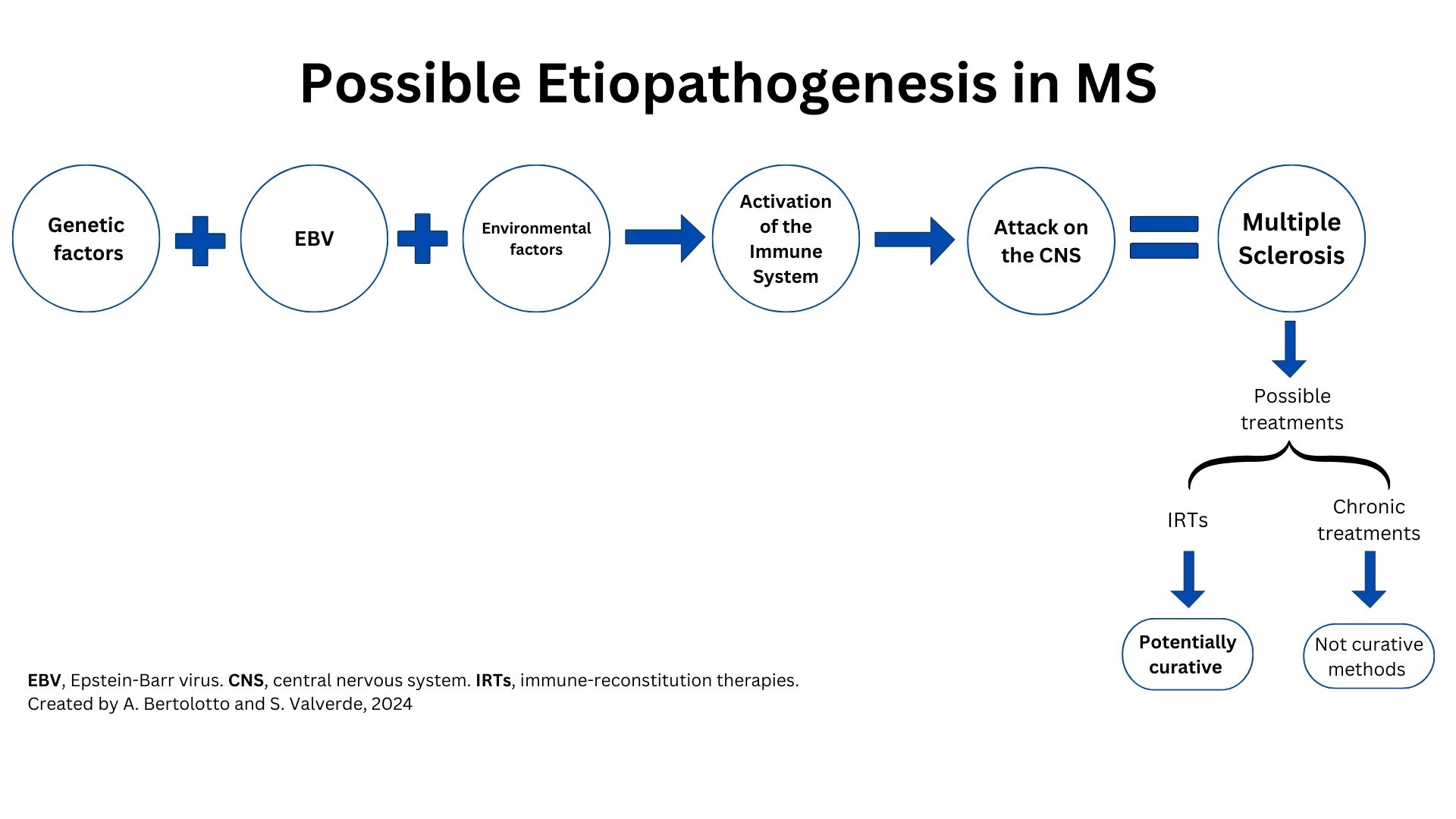

Etiopathogenesis of MS

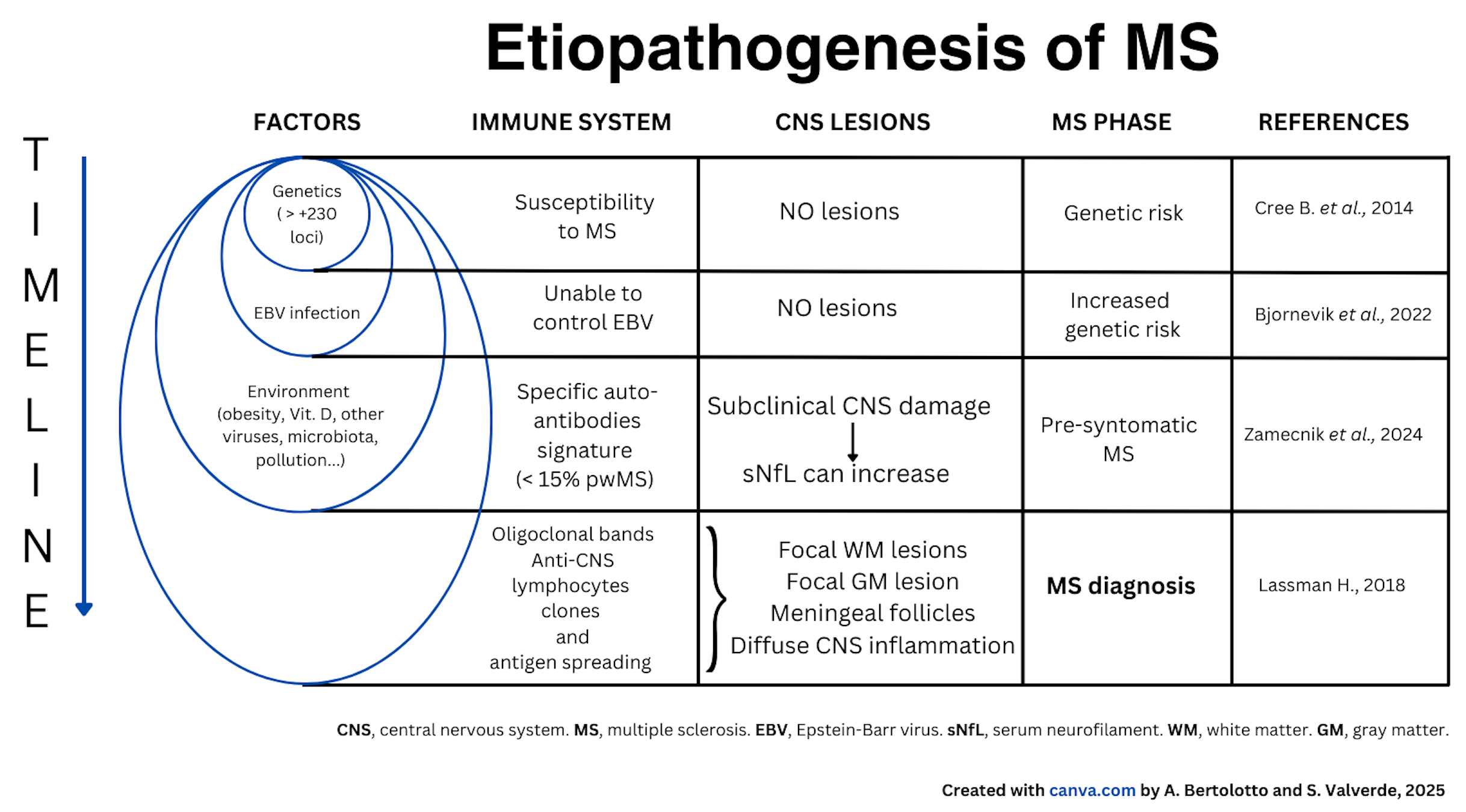

The figure below outlines the possible steps and factors believed to contribute to the development of MS. To develop MS, it is necessary, but not sufficient, to have both a genetic predisposition and to have contracted an infection with EBV, which is asymptomatic in most cases.

To these two conditions, environmental factors must be added, such as childhood obesity, vitamin D deficiency, smoking, environmental pollution, alterations in intestinal flora, and perhaps others yet unknown, and whose specific role is not yet defined. The combination of these conditions leads to modifications of the immune system which is responsible for defending our body against pathogens such as viruses and bacteria and consists of certain types of white blood cells (lymphocytes, monocytes), lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus.

The immune system in people who develop MS, in addition to carrying out its normal defense functions, also becomes aggressive toward the CNS. This activation occurs in different phases, which are not yet well defined.

First, the immune alteration involves the production of autoantibodies against the nervous system, which are detected in a minority of pwMS. Subsequently, lymphatic cells are formed that are auto-aggressive, meaning they can attack the nervous system, particularly the myelin.

Auto-aggressive lymphatic cells multiply (clones) under particular conditions, enter the CNS, and cause inflammation, which can lead to symptoms (new lesions evident on MRI, sometimes with neurological symptoms, i.e., clinical attacks or relapses).

The table below illustrates the factors that are important in the etiopathogenesis of MS, the modification of the immune system, the lesions in the CNS and the various stages of MS.

For more details about the etiopathogenesis of MS, click on the references below:

Immuno Reconstitution Therapies

Over the past 30 years, the therapeutic landscape for MS has evolved. The aim has radically changed from the 1990s when the goal was to simply reduce attacks to the current goal of achieving a complete and durable disease control (Lünemann et al., 2020).

AHSCT is not a DMTs, but a multi-step procedure.

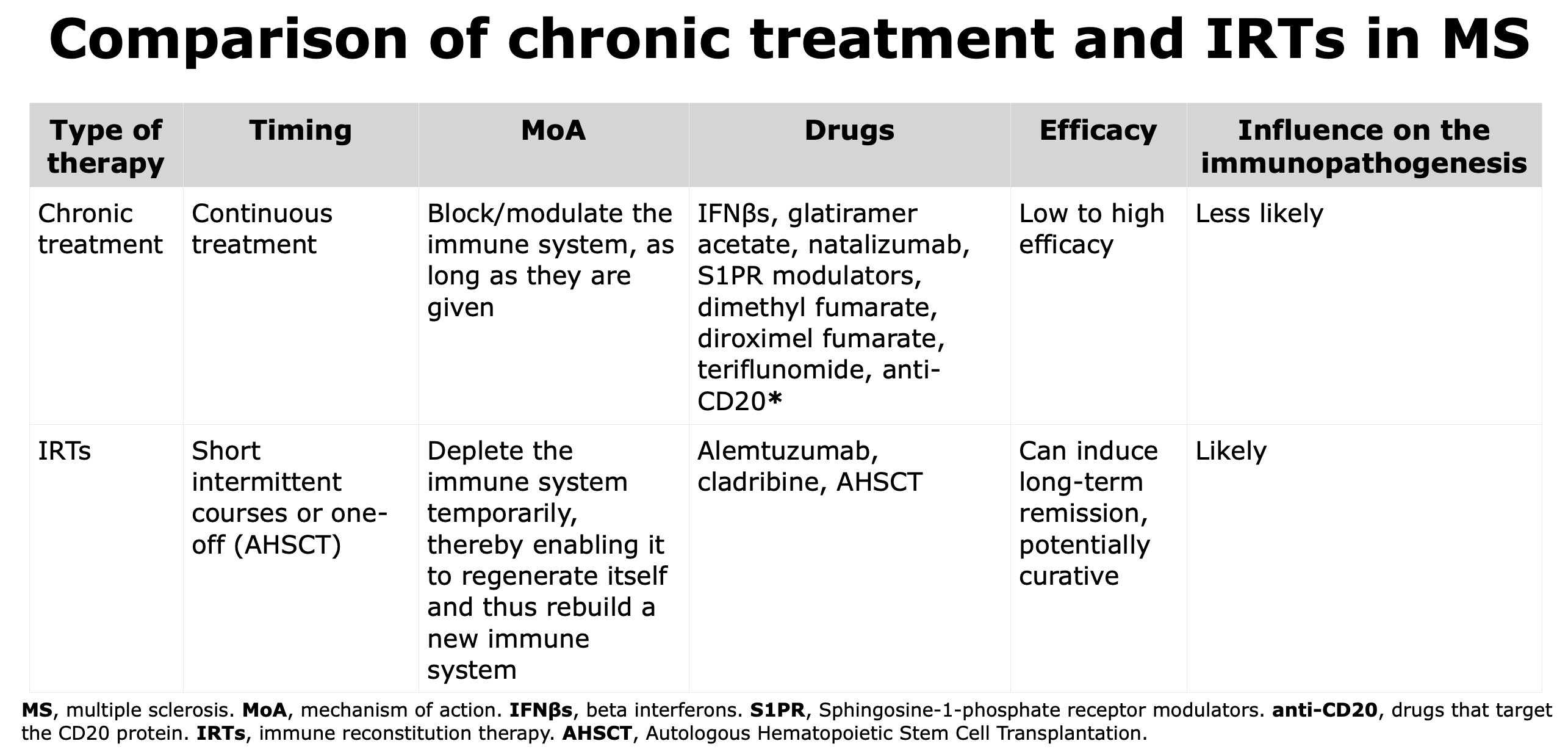

IRTs differ from chronic treatment for mechanism of action as they have the capacity to deplete the immune system temporarily, thereby enabling it to regenerate and reconstitute itself and thus rebuild a new immune system.

IRTs are able to reset the immune system, and the new immune system appears to be less aggressive against the CNS; this condition of low-aggressivity can last for years and explain why IRTs are used in short courses (Cladribine and Alemtuzumab) or only once (AHSCT).

When the efficacy, that is the capacity to reduce the risk of new relapses, of the IRTs is compared, AHSCT is more powerful than Alemtuzumab (Häußler et al., 2021; Braun et al., 2024) while Alemtuzumab is considered more efficacious than Cladribine.

AHSCT is a procedure where different protocols are utilized and can result in different efficacy and risks. Click here for the table comparing AHSCT with other DMTs.

*Some authors consider anti-CD20 therapies as IRTs, such as Lünemann et al., 2020

“

“